By John Tonin

Founded in 1986 by the Sisters of St. Joseph’s of Hamilton, The St. Joseph’s Health System International Outreach Program (IOP) will celebrate its 30th anniversary this year. It first formed through a small partnership with the government of Dominica and gradually expanded to start projects in Haiti in 1992, and Uganda in 1995.

Initially, the program sent Canadian doctors and nurses overseas to train local doctors and nurses. The program also donated equipment and supplies to countries where there were shortages. Today, the IOP also brings foreign medical professionals to Hamilton to train them in the latest in Canadian medicine so they can go home and share their new skills.

In 2010 the International Outreach Program received charitable status from the Canadian Revenue Agency. While there are other medical outreach programs in Canada, the IOP is unique.

“There are two things that are unique about the International Outreach Program,” said Director of Development Alan Sharpe. “One of them is our emphasis on training doctors to train doctors. We train them to get a faculty position at a university where they can train a doctor who will train a doctor, making the country’s health system grow exponentially. The second thing that is unique about our program is that the doctors are fully licensed and insured so they can do everything a Canadian resident does [while they are studying in Canada]. They can draw blood, order x-rays, prescribe medicine, deliver babies, set bones, and they can do operations. Other programs only offer an observership.”

Currently the IOP is working with three countries: Haiti, Uganda and Guyana.

“There is a doctor shortage in the developing world,” said Sharpe. “In some developing countries, there are 100,000 people and only one doctor – that is like Hamilton having five doctors. There is especially a shortage of doctors with specialties or sub-specialties like hematologists or pediatric nephrologists and that is why we bring the doctors to Canada.”

At present the doctors studying in Hamilton are from Uganda. The IOP has a partnership with four medical schools across Uganda and the focus is to grow the Ugandan medical program through an exchange program with McMaster University.

“If a doctor wanted to come to Canada to study, they would have to go through their faculty and be approved at the university level,” said Sharpe. “We do not just take any doctor, we make sure it is a doctor that the country actually wants. For example, in Kampala, the capital of Uganda, you have Makerere University, which is the medical school, and Mulago Hospital, a teaching hospital, and they work together. The clinical fellows that we get from Makerere University have all been vetted because the university decides that’s what the hospital needs, that’s what the university needs and that’s what the people of Uganda need.”

Doctor Anthony Batte arrived in Canada in October to study pediatric-nephrology – kidney diseases in children.

“The IOP is one of the key groups, along with McMaster, that has done a lot of work in training sub-specialists in the different fields of medicine,” said Batte. “Especially in the department of internal medicine, the sub-specialists that we have [in Uganda] are trained by McMaster. Right now I’m being trained to be a pediatric nephrologist and it’s a big achievement that the IOP has given us, for the university and the country.”

Batte is grateful for what the IOP is helping him to accomplish in obtaining his sub-specialty, but also for it helping grow the Ugandan medical system.

“I think we as a country, as Uganda, we need to acknowledge what the IOP has done,” said Batte. “The training that we get is key to the health system and to the government because they could not afford to do what the IOP does. The IOP takes on big ventures and it’s very important and it’s helping our health system.”

The Ugandan doctors who come to Canada train to become sub-specialists, a level of training they cannot obtain back home. Although they are studying and practicing in different fields of medicine, they all arrive in Canada with the goal of making their country’s medical system better when they return home.

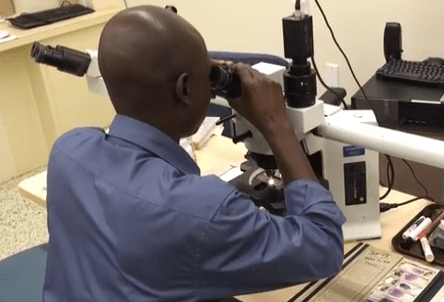

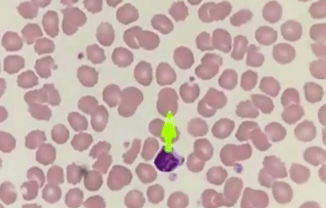

Dr. Clement Okello arrived in Hamilton in August. He is sub-specializing in hematology – the study of blood.

“There is a big gap in the field of hematology (compared to Canada) at the Uganda Cancer Institute,” said Okello. “Because of my interest in this discipline I was identified and came to McMaster University to take a course unit on internal medicine. Here I can super-specialize in hematology. They don’t offer this training in Uganda.”

Okello is working hard at his studies, but when he returns home his workload will increase drastically.

“Uganda is a small country with a population of 36-million people,” said Okello. “There is only one cancer institute so once I get home I’ll be teaching students as well as treating people. We get so many people coming to the institute. Our patients back in Uganda are so ill.”

Dr. Peace Bagasha also arrived in August. She works at Mulago Hospital as a nephrologist – a kidney specialist. She chose to study in Canada because of Uganda’s continued issues with kidney diseases.

“Kidney diseases are a huge, huge problem in Uganda,” said Bagasha. “In Uganda we not only have diabetes and hypertension, those are [just the] lifestyle illnesses. We have those but we also have a lot of infections like HIV. It’s pandemic in Uganda. The numbers are overwhelming for doctors looking after the kidneys. Kidney disease is like a death sentence for us.”

Geriatrician Dr. Harriet Nankabirwa points out the population of Uganda is aging. She teaches medicine at Makerere University and upon returning home she wants to get geriatrics into the school curriculum.

Nankabirwa says Uganda, with its population of 36-million people, does not have any geriatricians. According to the Canadian Medical Association, Canada, with a population of 35 million, has 248.

“The problem now is there is no interest in geriatrics,” said Nankabirwa. “Since there is no training, young doctors and senior doctors take the field for granted. When I return home I am going to try as much as possible to train the undergraduates. I am going to do this by lobbying with the dean of medicine for slots to incorporate tutorials about geriatrics. I will also mentor a few students.”

The IOP has trained over 95 Ugandan doctors, 98 per cent of them are still practicing medicine in Uganda. IOP alumni lead 75 per cent of sub-specialists at one site in Uganda and 60 per cent are in positions of leadership.

Besides bringing doctors to Canada to study in the latest in Canadian medicine, the IOP also travels to other countries to work in the hospitals. A hospital the IOP frequently visits is Centre Medical Beraca, in La Pointe, Haiti. The IOP will bring a team of volunteer doctors and nurses as well as supplies.

“Whenever we work in a country we work long-term. We build the relationship, the trust and we return many times during the year and we continue where we left off,” said Sharpe. “The key thing to remember about the IOP is that we only go to a country if we are invited, and we only offer the training, equipment, and supplies that they ask for. The last time we brought an obstetrician with us. Our volunteer helps mentor the Haitian obstetrician as well as helping him diagnose and deliver babies. We also brought an orthopedic surgeon with us and he spent time in the operating room, training a third-year Haitian orthopedic resident.”

Since the IOP has started working in Haiti, health care for mothers and babies has improved. The number of women receiving ante-natal and post-natal care has increased. There have also been reductions in infection rates, as well as the number of

Over its 30 years, the IOP has helped countries improve their health systems. The International Outreach Program would not be able to do what it does without the community’s contributions. If you wish to donate to the IOP click here